A dynamic character changes in a meaningful way—beliefs, values, or choices—by story’s end. A static character stays fundamentally the same. Both belong in strong books. The craft is choosing which serves your theme and market—and then making that choice visible on the page. Below, you’ll get crisp definitions, a no‑confusion take on “flat vs round,” research on why change hooks readers, a 2×2 matrix with a 10‑point rubric, and an editing checklist you can run tonight.

Dynamic vs static character—clear definitions you can use

A dynamic character undergoes meaningful internal change (beliefs, values, goals) driven by story events. A static character maintains a consistent core; the world or other characters change around them. Both can be richly drawn or thin—“dynamic/static” measures movement, not depth. What matters is that readers can see the change—or the principled refusal to change—on the page.

Flat vs round ≠ static vs dynamic

M. Forster says, “The test of a round character is whether it is capable of surprising in a convincing way; if it never surprises, it is flat.” Keep this depth test separate from the movement question of static/dynamic.

Encyclopaedia Britannica echoes the distinction for general readers: round characters are complex and often develop; flat characters are simpler. Use flat/round to judge depth; use static/dynamic to judge change over time.

Why dynamic change works on readers (and when a static lead is smarter)

Narrative transportation → belief shift. In controlled experiments, readers who were more transported into a story adopted story‑consistent beliefs and evaluated protagonists more favorably. Make the value shift visible in action, not just on the lips.

Attention + emotion → action. Research summarized in Harvard Business Review shows compelling stories sustain attention and trigger social‑bonding responses associated with empathy and pro‑social behavior. Build change around stakes that matter.

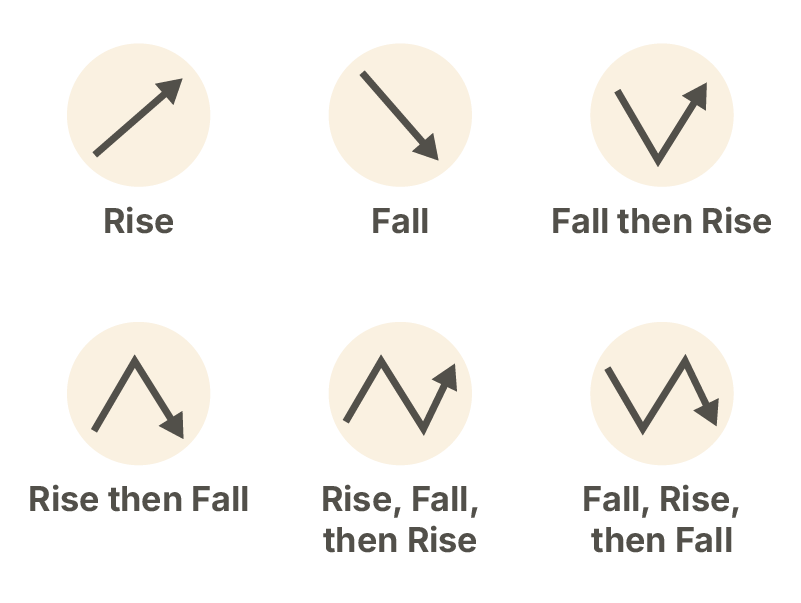

Six dominant emotional arcs. A computational analysis of 1,327 novels identifies six common emotional trajectories. Character change becomes most legible near an arc’s inflection points—your midpoint, crisis, or denouement. Plan where readers will feel the switch.

When a static center helps. In long‑running detective and procedural series, a recognizable, stable sleuth provides a consistent lens while cases, cultures, and eras churn. Route change to the cast, community, or world while the lead stays true.

Where change is expected. Genres like the Bildungsroman are built on formation—development of the protagonist over time. If you’re writing coming‑of‑age or upmarket growth narratives, a dynamic lead isn’t optional; it’s the point.

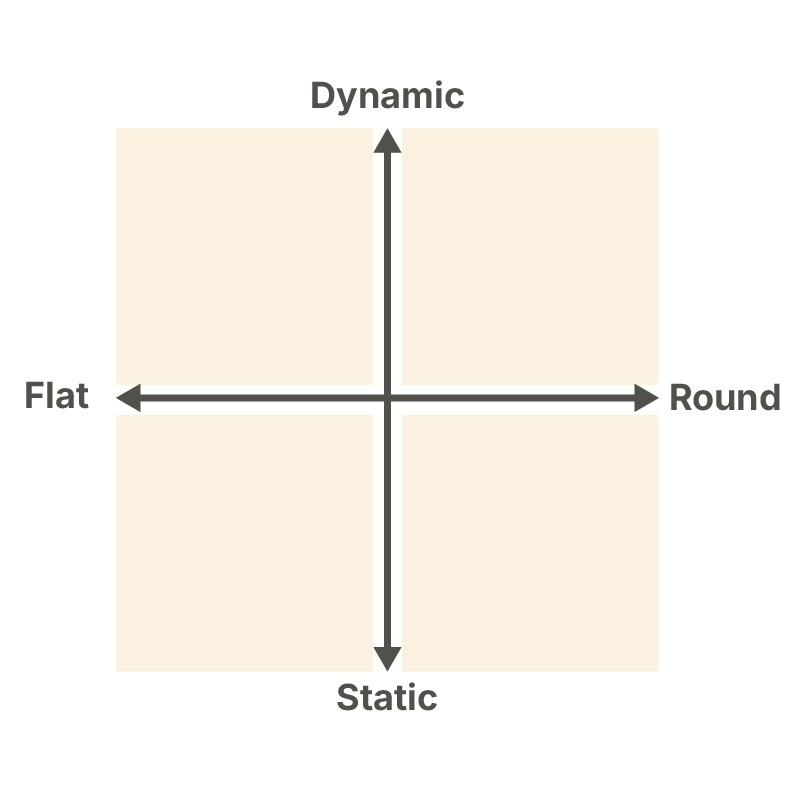

The Character Delta Matrix (2×2) and Quick-Check Rubric

Every memorable story balances depth—how complex a character feels—and change—how much they evolve.

Plot each major character on this grid:

Round–Dynamic: A layered person who truly changes (often your protagonist).

Round–Static: A rich, consistent anchor for the story or series.

Flat–Dynamic: A focused supporting role that pivots—think skeptic turned ally.

Flat–Static: A steady mentor, foil, or obstacle who keeps the spotlight on others.

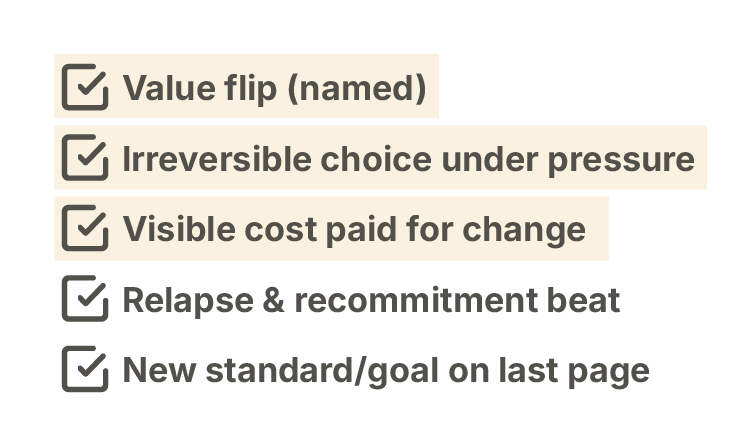

Once your cast is mapped, use this 10-point rubric to see who feels vivid and who still reads flat.

Score each major character out of 10—five points for Depth and five for Change.

Depth (0–5)

- Do their contradictions create tension?

- Is there a gap between what they show and what they hide?

- Do they want something concrete and testable?

- Does their past still influence present choices?

- Do they ever surprise the reader—and make it feel earned? (Forster’s test of a round character.)

- Do they undergo a clear reversal in belief or attitude?

- Do they make an irreversible choice when tested?

- Do they pay a visible cost for that decision?

- Do they stumble and recommit before the end?

- Do they finish with a new goal or moral standard that proves growth?

Change (0–5)

Most leads score around seven or higher. A static lead can work—especially in a series—but the story must show movement somewhere else.

How to Use It

Once you’ve scored your cast, look for patterns.

If scenes drag, ask: Is this character deep enough—or changing enough?

Move a character right on the grid by adding internal contradictions or richer motives.

Move them up by forcing decisions that reveal growth.

If two flat-static characters dominate a scene, raise the stakes or cut it.

The Matrix helps you see at a glance where emotional momentum is missing.

Revision Lab: Five Editorial Passes to Make Change Visible

After mapping your characters, use these passes to bring their arcs into focus.

- Belief-Shift Check

Identify where the character’s guiding belief changes.

If it never happens—or happens off-page—add pressure earlier so readers can witness the moment. - Transportation Test

Write one sentence for what your character believes at the start and one for the end.

Add the action that proves the difference.

If it’s invisible, clarify it in scene. - Action Over Assertion

Replace “I’ve changed” declarations with decisions that demonstrate it.

Readers believe what characters do, not what they say. - Opposition Redesign

If your lead remains steady, let a rival, ally, or the community evolve instead.

Their change keeps tension alive and mirrors the story’s theme. - Editorial Pass

A developmental edit should test motivation, escalation, and how theme drives choice.

Copyedits and proofs come later—first, ensure the emotional engine runs.

How It Looks in Practice

Leadership nonfiction: In Dare to Lead, Brené Brown reframes vulnerability from liability to courage and shows the shift through decisions and stories—not slogans. If your book aims to change how leaders act, make your evolving judgment visible on the page. A steady co-narrator or colleague voice can serve as a “round–static” anchor.

Memoir / personal growth: In Educated, Tara Westover’s inner stance changes before her outer life fully does; readers feel the turn because it’s dramatized in scenes and choices.

Fiction series: Sherlock Holmes, Miss Marple, and Jack Reacher mostly keep a consistent core; the world and cases change. Many modern series add a mentee or rival with a round–dynamic arc to keep renewal without breaking the brand.

Standalone fiction: A Christmas Carol makes Scrooge’s turn unmistakable—beliefs change, and new actions prove it: generosity, restitution, and altered relationships.

Final Takeaway

Dynamic and static characters both have purpose. The difference is intention: knowing which kind of motion serves your story.

Use the matrix to test your cast, the rubric to sharpen scenes, and these five passes to ensure readers feel the transformation, not just read about it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does my protagonist have to be a dynamic character?

No. Series and procedurals often use a round–static lead as a stable lens on changing cases, cultures, or eras. Route visible change to other characters or the community so the story still moves.

How is “dynamic vs static” different from “flat vs round”?

Flat/round measures complexity (Forster’s capacity to surprise convincingly); static/dynamic measures change over time. They intersect but aren’t synonyms.

Is there evidence that character change improves reader impact?

Yes. Narrative transportation research links immersion to belief and attitude change, and neuroeconomics findings explain why attention plus emotion prompt pro‑social action—supporting designs where meaningful change is visible on the page.

References (selected, authoritative)

- E.M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel — primary source for flat vs round (capacity to surprise convincingly).

- Encyclopaedia Britannica — overview of flat/round; detective story conventions.

- Oxford Reference / Oxford Research Encyclopedia — genre expectations for the Bildungsroman.

- Green & Brock (2000), Journal of Personality and Social Psychology — transportation and persuasion.

- Paul J. Zak (2014), Harvard Business Review — why good storytelling drives attention, empathy, and action.

- Reagan et al. (2016), EPJ Data Science — six dominant emotional arcs.

- Publishers Weekly — editing stages; why structural work precedes polish.

Ready to validate your character arcs with editors who’ve shipped bestsellers? Start your Manuscript Assessment today—and turn character change into reader change.